The Great American Lifestyle Inflation

How We Turned Wants Into Needs

My in-laws are in town this week. They are a family of five with a modest 3-bedroom, 1-bathroom home totaling 1,100 square feet. Their two youngest children share a room, like I did when growing up with my brothers. Growing up, our family car was a 1996 Honda Civic and all three boys sat in the back seat shoulder-to-shoulder. It was the same way for my parents in their 1970s sedans, even on road trip vacations. In our house, the whole family gathered around the dinner table each night for a home-cooked meal, and eating at a restaurant was a special occasion reserved for birthdays.

Today, that same lifestyle would feel like poverty to most Americans. We've convinced ourselves that we need walk-in closets, granite countertops, and restaurant meals several times per week. But this isn't progress. It's lifestyle inflation on a massive scale.

I’ve previously written about our changing culture, but I didn’t include as many examples as I do in this post so you can see exactly how much more we are consuming versus years past.

The Numbers Don't Lie: We Live Like Kings Compared to 1950

The transformation of American living standards since the 1950s isn't subtle. It's shocking.

Housing: Three Times the Space Per Person

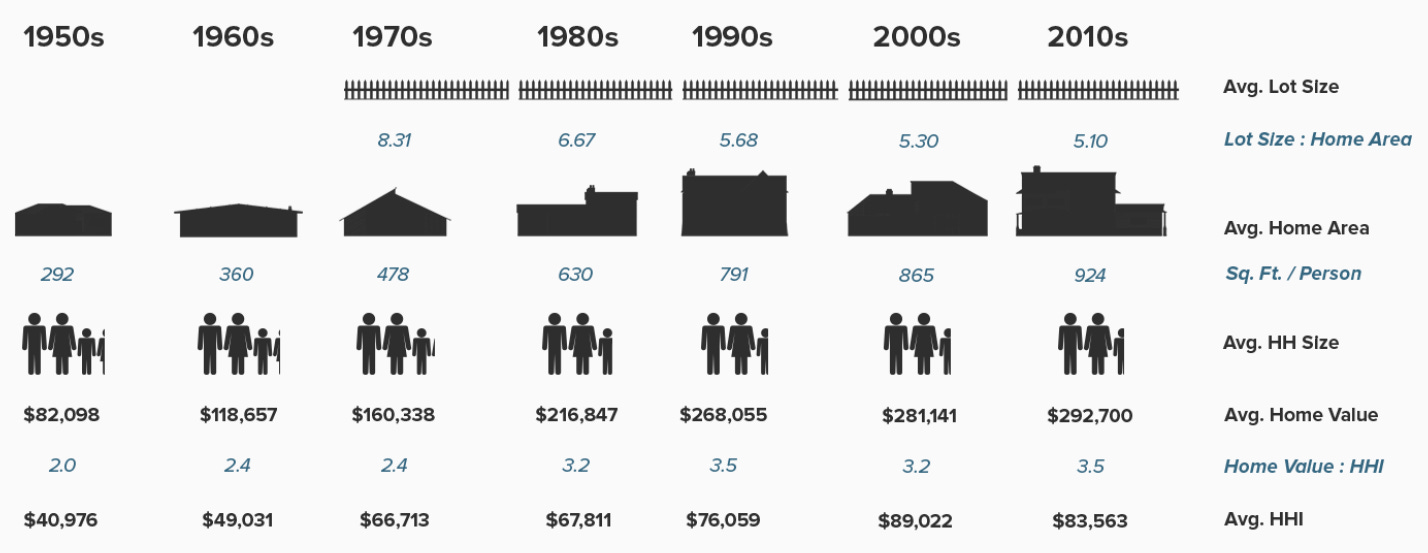

In the 1950s, the average new home was 983 square feet with 3.37 people per household, giving each person 292 square feet of living space. By the 2010s, the average new home expanded to 2,392 square feet with just 2.59 people per household—924 square feet per person. That's three times the personal space in just 60 years.

But we didn't stop there. Family sizes are shrinking, with recent CDC data showing yet another decrease in the fertility rate. Meanwhile, good luck finding a starter home you can afford in 2025.

Cars: When Compact Became Enormous

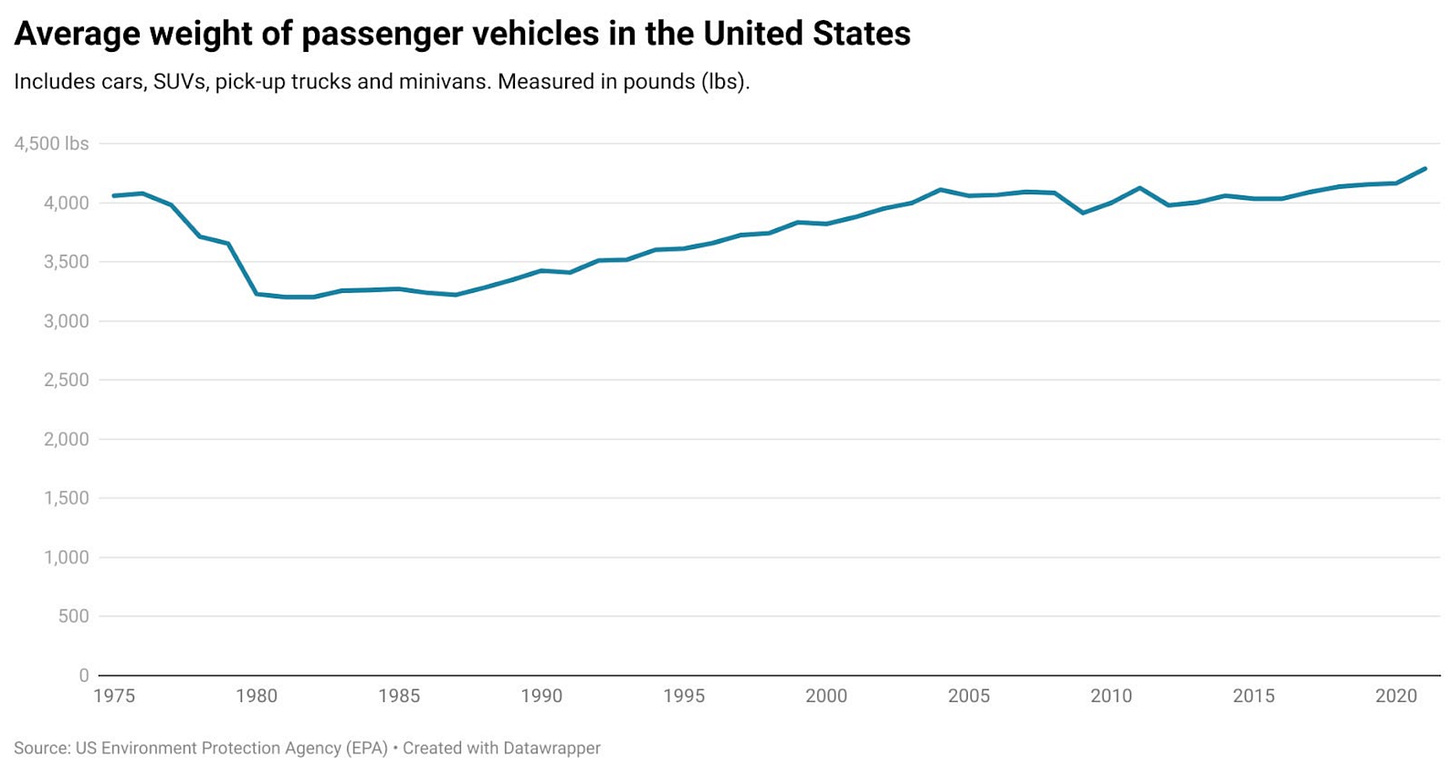

Average American car in 1980: 3,250 pounds

Average American car in 2021: 4,250 pounds (+31%)

The Honda Civic perfectly illustrates automotive lifestyle inflation. The 1973 Civic measured 140.9 inches long and 59.3 inches wide. By 2008, the "compact" Civic had grown to 169.3 inches long and 69.0 inches wide. Today's 2026 Civic is 184.8 inches long and 70.9 inches long. This is longer than many full-size cars from the 1970s.

The Mini Cooper shows even more dramatic expansion. The 1959 original weighed 1,357 pounds and was truly mini. Today's version weighs 3,014 pounds, a 222% weight increase.

Yes, modern cars include genuine safety improvements like airbags and crumple zones, but the size inflation goes far beyond safety requirements. We've simply decided that bigger is better, consequences be damned. (Worse fuel economy, more damaging, more materials, larger parking spaces, etc)

Dining Out: From Special Occasion to Daily Routine

The most dramatic cultural shift might be how we eat. In 1960, Americans spent 3.3% of disposable income on food away from home. By 2019, this had risen to 4.7%. (Source: USDA Economic Research Service) But the raw numbers miss the cultural transformation.

A woman who grew up in the 1950s and 1960s recalls that her middle-class family never went out to eat except on vacation. Her mother, shaped by Great Depression values, would have considered ordering takeout "a foolish waste of money." Home-cooked meals weren't just common. They were universal. (Source: The Cultural Revolution of Eating Out, Medium)

Today, Americans spend roughly the same amount on restaurant food as they do on groceries. (Source: Our World in Data) The average American now orders takeout or delivery 4.5 times per month and dines at restaurants 3 times per month. We've turned what was once a special treat into routine consumption. (Source: US Foods Survey 2024)

Clothing: Five Times More Stuff We Don't Wear

From the 1900s through the 1950s, Americans spent 12-14% of their annual income on clothing. Today, we spend about 3%. You might think we're being more frugal, but you'd be wrong. We actually own more than five times as many clothing items as people did in the first part of the 20th century. (Source: Quartz - The Case for Fewer But Better Clothes)

A 1950s middle-class woman's complete wardrobe included three wool dresses, three cotton dresses, one formal dress, one afternoon dress, one lightweight coat, one winter coat, and one raincoat. That's it. Her entire wardrobe fit in a closet the size of today's coat closet. (Source: Vintage Dancer - 1950s Capsule Wardrobes)

Compare that to today's average of 118-148 clothing items per person. (Source: Green Heart Collective UK survey, Capsule Wardrobe Data US survey) We have walk-in closets larger than 1950s bedrooms, stuffed with clothes we barely wear. The average person wears only 20% of their wardrobe 80% of the time, meaning vast amounts of clothing and closet space sit unused.

Weddings: When "I Do" Became "I Spend"

Even our celebrations have inflated beyond recognition. In the 1930s, couples spent an average of $392 on weddings (about $6,481 in today's dollars), roughly 25% of annual household income. Today's average wedding costs $30,000, representing about 50% of median household income. (Source: Quartz - The 80-Year Tradition of Expensive American Weddings)

The 1930s couple's reception was simple: 70% of couples didn't even have one. Those who did spent about $714 in today's dollars. Now we consider elaborate receptions, professional photographers, wedding planners, and destination bachelor parties to be standard requirements.

Categories That Didn't Exist: Manufacturing Needs

Beyond inflating existing categories, we've created entirely new ones. In the 1950s, nobody bought bottled water, hired personal trainers, paid for pet daycare, or subscribed to streaming services. Coffee came from home, not $5 cups from cafes on every corner.

We've convinced ourselves these aren't luxuries but necessities. We "need" our daily Starbucks, "need" premium gym memberships, "need" subscription boxes delivered to our oversized homes with walk-in closets full of clothes we don't wear.

How We Got Here: The Manufacturing of Desire

This transformation didn't happen accidentally. It was engineered. (I mentioned this in-depth here.)

After World War II, American culture underwent a deliberate shift from thrift to consumption. Government and corporate messaging presented spending as patriotic duty. The "good purchaser devoted to 'more, newer and better' was the good citizen," as historian Lizabeth Cohen explained, "since economic recovery depended on a dynamic mass consumption economy." (Source: Advertising Educational Foundation)

Television amplified this message, showing Americans that the "normal" life included suburban houses, multiple cars, and every modern appliance. Advertising created artificial desires for things people had never needed before. The "democratization of desire" meant everyone was told they deserved the good life, regardless of ability to afford it. (Source: MIT Press Reader - A Brief History of Consumer Culture)

This cultural programming worked. We went from a society that viewed debt as shameful and waste as sinful to one that celebrates lifestyle upgrades and sees spending as self-care.

The Real Cost of Living Large

All this lifestyle inflation comes with hidden costs that compound over decades:

Environmental Impact: Bigger homes require more energy to heat and cool. Heavier cars burn more fuel. Disposable fashion creates textile waste. Our lifestyle inflation is environmentally unsustainable.

Financial Burden: Every upgrade extends the time needed to achieve financial independence. The difference between a 1,200 square foot home and a 2,400 square foot home isn't just the mortgage. It's property taxes, utilities, maintenance, insurance, and furnishing costs that last for decades.

Social Pressure: When bigger becomes normal, anyone choosing smaller feels deprived. We've created a cultural arms race where keeping up requires constant spending increases.

The Path Back to Sanity

The good news? This lifestyle inflation isn't inevitable or irreversible. People lived fulfilling lives with less for most of human history. Some changes since the 1950s represent genuine progress: better medical care, improved safety features, expanded opportunities. But most represent manufactured desire convincing us that wants are needs. (Do you truly need 30+ t-shirts or are five enough?)

Consider what your grandparents achieved with less: they raised families, built communities, and found happiness in homes half the size of today's average, with cars a fraction of current weights, and wardrobes that fit in actual closets.

You don't need to live like it's 1950, but you can stop pretending that every lifestyle upgrade is a necessity. Question whether bigger is actually better. Ask whether conveniences that didn't exist 70 years ago are truly essential now.

The most radical act in modern America might be choosing enough.

This post is part of an ongoing series examining how cultural messages around money affect our wealth-building efforts. What surprised you most about these lifestyle inflation trends? Share your thoughts in the comments.